Complications: Abortion’s Impact on Women

Spiritual and psychological healing after abortion

Grief after pregnancy losses such as miscarriage or stillbirth is a widely accepted psychological phenomenon.1 However, the grief experienced after induced abortion has been largely dismissed.2 Women suffering grief after an abortion are often unable to publicly express their sadness and are therefore at greater risk of experiencing complicated grief, a state in which sorrow, numbness, guilt and anger following a loss are long-lasting and interfere with the life of the grieving person.3

Women may rely on a variety of forms of assistance throughout their healing journey. Healing can take place with the help of organizations, individuals, and online resources. One example is Abortion Recovery International (ARIN), a world-wide organization that links post-abortion sufferers with professional services, resources and programs that are “personal, confidential, non-judgmental and open to all.”4 These programs range widely, as each woman has her own unique circumstances and personal beliefs. Other available resources include religious support groups, pregnancy resource centres, and online assistance, such as Abortion Changes You.

Forgiveness is considered an essential part of healing after abortion, regardless of one’s attitude towards abortion.5 Many women have unresolved feelings of shame and guilt, which can be lessened through forgiveness of themselves and of the other people involved in the abortion.6 Different religions have distinct approaches to forgiveness after abortion. Project Rachel, a Catholic ministry, involves steps such as recounting one’s story, assuring oneself of God’s mercy, and forgiving oneself. The Buddhist practice of mizuko kuyo encourages parents to write letters of apology, accepting responsibility for ending their child’s life.7 In addition to forgiveness, memorializing the child, perhaps by naming him or her, is an important step in healing.

- Perinatal Bereavement Services Ontario. December 2012. http://pbso.ca/main/?page_id=6.

- Speckhard A, Rue V. Complicated mourning: dynamics of impacted post abortion. Pre- and Peri-natal Psychology Journal 1993; 8(1): pp. 5-32.

- Complicated Grief. Mayo Clinic. December 2012. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/complicated-grief/DS01023.

- abortionrecovery.org.

- Hess RF. Healing after abortion: a search for forgiveness. Journal of Christian Nursing 2009; 26(3): pp. 154-58.

- Wilson K, Haynie L. Experiences of Women Who Seek Recovery Assistance Following an Elective Abortion: A Grounded Theory Approach. DNS dissertation, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center School of Nursing, 2004.

- Wilson JT. Mourning the unborn dead: American usage of Japanese Buddhist post-abortion rituals. http://udini.proquest.com/view/mourning-the-unborn-dead-american-goid:304844080/.

Maternal and infant mortality: a global perspective

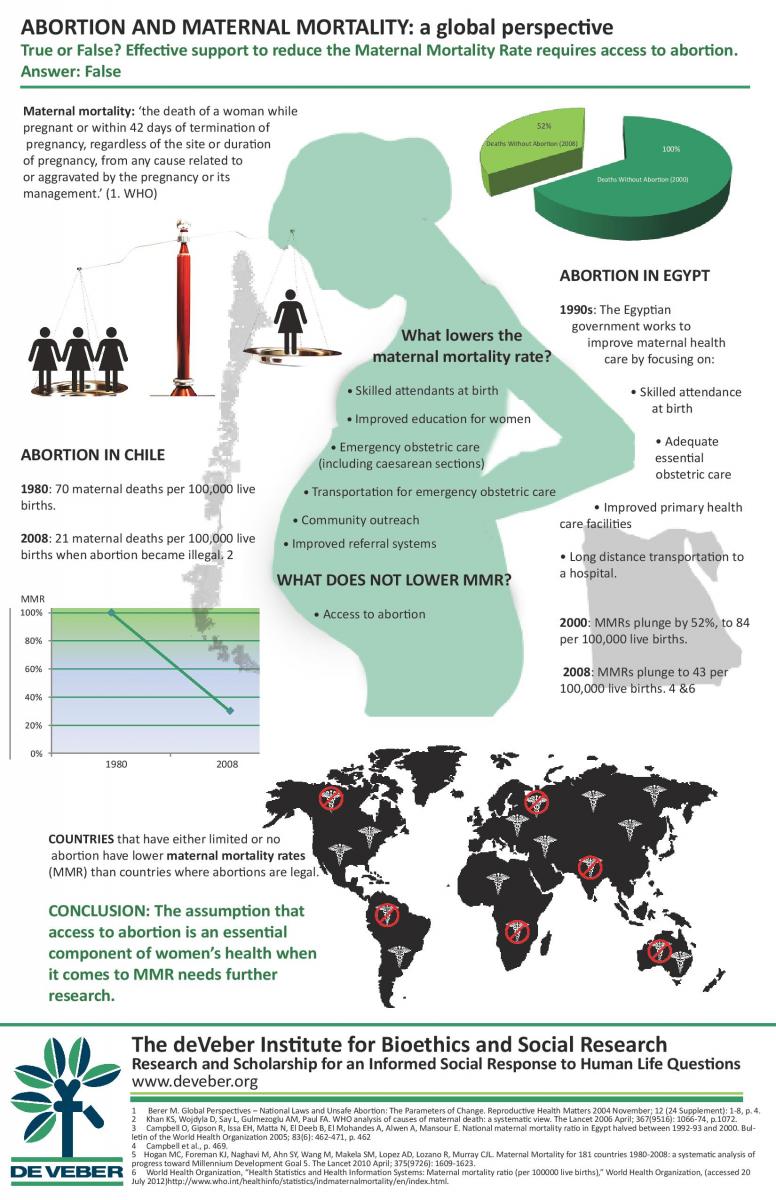

It is often argued that legalizing abortion is necessary to limit maternal mortality. However, evidence from around the world shows otherwise. A global analysis reveals that countries in which abortion is restricted have, in fact, lower maternal mortality rates (MMRs) than countries in which abortion is legalized. Additionally, countries with high mortality rates from unsafe abortion also have “the least effective and accessible health care services, making complications and deaths from unsafe abortion more likely.”1

Chile has one of the lowest MMRs in the Americas.2 Its MMR (defined as number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) decreased by 70 per cent after abortion was banned.3 In contrast, after legalizing abortion, Guyana’s MMR decreased by only 32 per cent.4 This trend is confirmed by El Salvador and Nicaragua, which both had significant decreases in MMR after banning abortion.5 Egypt and the Ugandan district of Soroti also have restrictive abortion laws and have had a decrease in MMR of 52 per cent and 75 per cent, respectively.6 In contrast, South Africa legalized abortion in 1996 and has actually seen a slight increase in its MMR, including an increase in deaths due to abortion, from 114 in 2002-4 to 136 in 2005-7;7 the country is considered to be making “no progress” in improving maternal health.8

Across the globe, factors that are known to decrease MMR include increased education for women, better health care, skilled attendance at birth, emergency obstetric care, primary health care facilities improvement, and long distance transportation to a hospital.9

These findings challenge the notion that abortion improves maternal health, and have powerful implications for policies aimed at decreasing maternal mortality.

- Berer M. Global perspectives – national laws and unsafe abortion: the parameters of change. Reproductive Health Matters 2004 November; 12(24 Supplement): 1-8, p. 4.

- 2.Population Division of the United Nations Secretariat. Abortion policies: a global review – Chile. United Nations Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2002. Online edition:

- 1.Berer M. Global perspectives – national laws and unsafe abortion: the parameters of change. Reproductive Health Matters 2004 November; 12(24 Supplement): 1-8, p. 4.

- 2.Population Division of the United Nations Secretariat. Abortion policies: a global review – Chile. United Nations Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2002. Online edition:

- 1.Berer M. Global perspectives – national laws and unsafe abortion: the parameters of change. Reproductive Health Matters 2004 November; 12(24 Supplement): 1-8, p. 4.

- 2.Population Division of the United Nations Secretariat. Abortion policies: a global review – Chile. United Nations Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2002. Online edition: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/abortion/index.htm. Ruiz-Rodríguez M, Wirtz VJ, Nigenda G. Organizational elements of health service related to a reduction in maternal mortality: the cases of Chile and Colombia. Health Policy 2009 November; 90(2-3): pp. 149-155.

- 3.Hogan MC, Foreman KJ, Naghavi M, et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries 1980-2008: a systematic analysis of progress toward Millennium Development Goal 5. The Lancet 2010 April; 375(9726): pp. 1609-23.

- 4.Ibid., p. 1615.

- 5.Mendieta W, Bohemer L, Cabrera RJ. Nicaragua and abortions. (Letter). Washington Times. December 20, 2007.

- 6.Campbell O, Gipson R, Issa EH, et al. National maternal mortality ratio in Egypt halved between 1992-93 and 2000. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2005; 83(6): 462-71, p. 469; World Health Organization. MPS: Making Pregnancy Safer – Implementing the MPS Initiative in Soroti district, Uganda.World Health Organization, 2010; p. 24.

- 7.National Committee on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths (NCCEMD). Saving mothers 2005-2007: fourth report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa: expanded executive summary. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health, 2008 March, p. 12.

- 8.Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank estimate. World Health Organization, 2012; p. 44.

- 9.Gonzalez R, Requejo JH, Nien JK, Merialdi M, Bustreo F, Betran AP. Tackling health inequities in Chile: maternal, newborn, infant, and child mortality between 1990 and 2004. American Journal of Public Health 2009; 99(7): 1220-1226, p. 1225.; Koch E, Thorp J, Bravo M, Gatica S, Romero CX, Aguilera H, Ahlers I. Women’s education level, maternal health facilities, abortion legislation and maternal deaths: a natural experiment in Chile from 1957 to 2007. PLoS ONE 2012 May; 7(5): p. e36613; Schuberg K. Abortion Ban Does Not Mean More Maternal Deaths, Chilean Study Finds. CNS News. 25 July 2012. http://cnsnews.com/news/article/abortion-ban-does-not-mean-more-maternal-deaths-chilean-study-finds.

So many missing girls: abortion and sex selection

The rise of prenatal testing to determine sex, along with pre-existing social beliefs, has allowed for sex-selective abortion to become widespread across the globe. It has recently been determined that more than 160 million girls are “missing”, mainly in Asia. This circumstance is due in large part to “gendercide” via sex-selective abortion, the systematic killing of females before birth. Sex-selective abortion has contributed to gender imbalance as the sex ratio at birth (SRB), which is the number of male births for every 100 female births, has been skewed from the normal range of 103 to 107 up to 160 and 200 in some regions.1 The explanation for this phenomenon is straightforward: with the technological advancements of ultrasound and amniocentesis came the possibility of aborting the unborn according to their sex. As UNICEF explains, “Where there is a clear economic or cultural preference for sons, the misuse of these techniques can facilitate female foeticide.”2

Female foeticide is especially prevalent in China and India, where male children are favoured due to sociocultural biases and/or the financial burden of having a female child. According to China’s 2010 census, the country’s SRB was 118, soaring as high as 135 in some rural areas, resulting in 32 million more males than females under the age of twenty.3 In India, there are about 7.1 million fewer girls than boys aged six and under.4 Sex-selection has begun to spread to the West, especially Canada.5

The ethical and social impact of sex-selective abortion is beginning to manifest, as girls are now being abducted and sold for marriage in remote rural regions.6 The loss of over 160 million girls is not only a direct, sexist attack on the female half of the human race, but has left the remaining women more vulnerable as men begin to confront the marriage squeeze.

- Das Gupta M, Chung W, Shuzhuo L. Evidence for an incipient decline in numbers of missing girls in China and India. Population and Development Review; 35(2): p. 412.

- UNICEF. State of the world’s children 2007: women and children: the double dividend of gender equality. New York: UNICEF House, 2006. Online edition: http://www.unicef.org/sowc07/report/report.php.

- Zhou C, Wang XL, Zhou XD and Hesketh T. Son preference and sex-selective abortion in China: informing policy options. International Journal of Public Health 2012; 57(3): pp. 459-65. Zhu WX, Li L, Hesketh T. China’s excess males, sex selective abortion, and one child policy: analysis of data from 2005 national intercensus survey. BMJ 2009 April; 338(b1211): p. 1.

- Sahni M et al. Missing girls in India: infanticide, feticide and made-to-order pregnancies? Insights from hospital-based sex-ratio-at-birth over the last century. PLoS ONE 2008; 3(5): p. 3.

- Vogel L. Sex selection migrates to Canada. CMAJ 2012; 184(3): p. e163.

- Milliez JM. Sex selection for non-medical purposes. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 2007; 14(S1): pp. 109-13.

Has abortion reduced the crime rate?

Two American economists, Donohue and Levitt, have argued that the complete legalization of abortion in the US between 1967 and 1973 resulted in a significant drop in the crime rate from the 1990s onward. As Levitt reasons, “Legalized abortion led to less unwantedness; unwantedness leads to high crime; legalized abortion, therefore, led to less crime.”1

However, this argument has been challenged by other economists, who note several errors in Donohue and Levitt’s calculations and findings. Some contend that the decreased crime rate can be linked to the simultaneous decline of the crack-cocaine epidemic.2 Others challenge Donohue and Levitt for failing to separate criminals into age categories, since the decrease in crime actually occurred among older cohorts rather than those born after the legalization of abortion. In fact, crime has been increasing among these younger cohorts.3 Another challenge to Donohue and Levitt’s findings is that since abortion was legalized in the UK, crime rates there have risen.4

Researchers have also pointed out that the rise in abortion since its legalization has increased the incidence of single motherhood,5 in part because treating abortion as a method of birth control enables men to opt out of commitment. Since the children of single-parent families are at higher risk of criminal behaviour than those of two-parent families, it is more likely that the rise in abortions has increased, rather than decreased, the crime rate. Additionally, high-risk mothers are less likely to abort than low-risk mothers.6

Much of the research done in the past decade casts doubt on whether Donohue and Levitt’s supposed link between abortion and falling crime rates exists at all.

- Levitt SD, Dubner SJ. Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. New York: William Morrow, 2006: p. 127.

- Joyce T. Did legalized abortion lower crime? Journal of Human Resources 2004; 39(1): 1-28, pp. 2-4

- Lott JR, Whitley J. Abortion and crime: unwanted children and out-of-wedlock births. Economic Inquiry 2007; 45(2): p. 308.

- Kahane LH, Paton D, Simmons R. The abortion-crime link: evidence from England and Wales. Economica. February 2008; 75(297): p. 2.

- Ibid.

- Joyce, p. 26.

Informed consent: a woman’s right

The concept of informed consent is a longstanding legal principle that patients may not be subjected to medical procedures without receiving full disclosure of risks and giving their consent. Though disclosure is now an ethical and legal obligation throughout most of the Western world, its application to abortion cases has been controversial. This is due in part to dispute over the risks of abortion, and in part to the difficulty of enforcing informed consent.

Both the American and Canadian Medical Associations require their members to provide patients with information concerning risks and alternatives before asking them to consent to a medical procedure. However, punishment for not doing so is unclear. Failure to inform a patient of risks or possible alternatives constitutes neither an injury in itself, nor professional misconduct. Thus, it is difficult to prosecute a physician for failing to obtain a patient’s informed consent to a medical procedure, particularly abortion.

Informed consent cases generally fall under the category of negligence—the failure to provide due care to patients (rather than an intentional action that violates the patient’s bodily integrity).1 In order to sue successfully, the patient must demonstrate five elements of negligence: duty (that the physician actually had the duty to inform), breach of duty (that the physician did not inform), decision-causation (that the patient would have made a different decision had she been informed), injury (that the patient suffered resulting physical injury), and injury-causation (that the patient suffered a risk of which she was not informed or that an undisclosed alternative would have prevented injury).2 Each is addressed by jurisdictional laws, such as ‘Right to Know’ laws that make physicians legally liable for failing to provide their abortion patients with alternatives, ultrasounds, and other information.

However, the enforcement of these laws often requires the individual to sue. Unfortunately, this route is not often pursued by individuals for reasons such as guilt surrounding the abortion, lack of knowledge of legal rights, and financial constraints.Consequently, physicians have little incentive to inform their patients of the risks of induced abortion. Lawsuits based on failure to disclose the risks of abortion are rare in both the US and Canada. Recently, however, several suits have been brought against Planned Parenthood for failing to secure informed consent before performing an abortion.

- Morgan v. MacPhail, 550 Pa. 202, 704 A.2d 617 (1997); Reibl v. Hughes, [1980] 2 S.C.R. 880.

- Faden RR and Beauchamp TL. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986: p. 29.

Immediate physical complications of abortion: an overview

The physical complications of induced abortion fall into two categories: immediate (occurring up to six weeks after the procedure) and late (occurring weeks, months, or years later). Immediate complications include hemorrhage, retained tissue, infection, uterine perforation, cervical laceration, and immediate psychiatric morbidity. Another immediate complication is unsuccessful abortion, which means either that the procedure has to be repeated, or the child carried to term is often damaged. The longer-term complications include infertility, premature birth, ectopic pregnancy, placenta previa and breast cancer.

Immediate complications occur in 3.4 to 11 per cent of surgically-induced abortions, depending on the jurisdiction. It is difficult to calculate the exact rate of complications, as abortion numbers are chronically underreported in the US and Canada.

Medical (drug-induced) abortion carries up to a four times higher risk of adverse outcomes, especially bleeding, than surgical abortion. A study from Finland showed that the percentage of women with complications after medical abortion was twenty per cent, but only 5.6 per cent after surgical abortion.1

Some risk factors for physical complications include age below twenty years, parity (number of pregnancies), previous induced abortions, women living in rural areas, gestational age, and method of abortion.2

- Niinimaki M, Pouta A, Bloigu A, Gissler M, Hemminki E, Suhonen S, Heikinheimo O. Immediate complications after medical compared with surgical termination of pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009; 114(4): pp. 795-804.

- Zhou W, Nielsen GL, Moller M and Olsen J. Short-term complications after surgically induced abortions: a register-based study of 56 117 abortions. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 81(4); 2002: pp. 331-6.

Biology and epidemiology confirm the abortion-breast cancer link

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death of women worldwide. It has been well-established that carrying a pregnancy to term decreases the risk of breast cancer. However, chiefly for political reasons, the link between abortion and breast cancer is highly disputed in North America, despite 57 studies that show a positive association between abortion and breast cancer, of which 23 are statistically significant.1 17 studies show no link, but many of them have been criticized for their methodology.

Research has revealed that the longer a woman waits to have her first full-term pregnancy, the higher her risk of breast cancer, as her immature, cancer-vulnerable breast tissue is exposed to carcinogens for a longer duration.2

Additionally, there is evidence that induced abortion before 32 weeks gestation independently increases breast cancer risk. Confirmed by several studies, this link is explained by breast physiology.3 After conception, the embryo releases a hormone that causes an increase in estrogen and progesterone, which in turn cause breast cells to multiply. These new breast cells remain immature and cancer-vulnerable until after 32 weeks gestation, when 85 per cent of them mature into non-vulnerable cells.4 If a woman obtains an induced abortion before 32 weeks gestation, she retains the multiplied cancer-vulnerable breast tissue, making her more susceptible to breast cancer.

Various epidemiological studies confirm the abortion-breast cancer link and meet the Bradford-Hill criteria for establishing causality. In fact, abortion has been documented as the greatest predictor of breast cancer in nine countries.5

The effect of abortion on breast cancer risk must be publicized so that women can be fully informed before consenting to abortion.

- See Ch. 7 of Complications: Abortion`s Impact on Women.

- Clavel-Chapelon F, Gerber M. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk: do they differ according to age at diagnosis? Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2002 March; 72(2): pp. 107-15.

- E.g. Dolle JM, Daling JR, White E, et al. Risk factors for triple-negative breast cancer in women under the age of 45 years. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention 2009 April; 18(4): pp. 1157-66. Naieni KH, Ardalan A, Mahmoodi M, Motevalian A, Yahyapoor Y, Yazdizadeh B. Risk factors of breast cancer in north of Iran: a case-control in Mazandaran province. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2007; 8(3): pp. 395-8.

- Russo J, Lynch H, Russo IH. Mammary gland architecture as a determining factor in the susceptibility of the human breast to cancer. The Breast Journal 2001 September; 7(5): pp. 278-91.

- Carroll P. The breast cancer epidemic: modeling and forecasts based on abortion and other risk factors. Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons 2007 September; 12(3): pp. 72-8.

Prenatal testing and abortion for fetal anomaly

Prenatal genetic diagnosis, while still a relatively new practice, is tracked through public health programs globally. Despite the many technological advances in testing for genetic anomalies, there is inconsistency in surveillance reports.1 While some maintain that the purpose of prenatal testing is to evaluate preventative measures, statistics show that the information collected about congenital conditions is leading to an increase in selective abortion.2

Prenatal testing began in the late 1970s with the use of amniocentesis to identify fetuses with Down syndrome or spina bifida. In addition to identifying chromosomal anomalies, prenatal screening can detect non-heritable conditions. The capacity to diagnose prenatally is now vastly disproportionate to the capacity to treat the illnesses or disabilities. Rather than preventing or treating a condition, the tests are often used to prevent the birth of individuals with certain undesired characteristics through termination of pregnancy. For example, the abortion rate for Down syndrome is 48.1 per cent across 16 European countries and is 98 per cent in Denmark.3

Now that prenatal screening is standard practice, women are often unaware they can refuse testing, and those who do are often seen as failing to “ensure the birth of a healthy child.”4 Additionally, those who carry a disabled fetus to term often are not provided with support or encouragement. As one author states, “disability rights advocates are right to think of genetic counselling as a search and destroy mission because testing will likely ultimately lead to greater intolerance of disabilities and less money for research or treatment.”5 Finally, although some women experience adverse psychological outcomes after terminating for fetal anomaly, many are not informed of this risk.6

- Lowry RB. Congenital anomalies surveillance in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2008; 99(6): pp. 483-5.

- Ibid., p. 483.

- Khoshnood B, Greenlees R, Loane M, Dolk H and EUROCAT Working Group. Paper 2: EUROCAT public health indicators for congenital anomalies in Europe. Birth Defects Research Part A (Clinical and Molecular Teratology) 2011; 91(Suppl 1): pp. S16-22. Nordvig L, Secher NJ, Andersen S. Psykologiske aspekter, brugerholdninger og – forventninger I forbindelse med ultralydskanning I graviditeten. Medicinsk Teknologivurdering 2006; 6(13): p. 12.

- Seavilleklein V. Challenging the rhetoric of choice in prenatal screening. Ph.D dissertation. Halifax, NS: Dalhousie University, 2008.

- Dixon DP. Informed consent or institutionalized eugenics? How the medical profession encourages abortion of fetuses with down syndrome. Issues in Law & Medicine 2008; 24(1). p. 21.

- Korenromp MJ, Page-Christiaens GC, van den Bout J, Mulder EJ, Hunfeld JA, Potters CM, Erwich JJ, van Binsbergen CJ, Brons JT, Beekhuis JR, Omtzigt AW, Visser GH. A prospective study on parental coping 4 months after termination of pregnancy for fetal anomalies. Prenatal Diagnosis 2007; 27(8): pp. 709-716.

[/fusion_fontawesome]Chapter 8 Summary

Physical complications: infection and infertility

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) is an infection that occurs when bacteria from the vagina or cervix move up into the uterus, uterine tubes, or ovaries. Women who undergo an induced abortion later suffer an up to ten per cent higher rate of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) than the general population.1 PID following a pregnancy termination can be caused by operative injury, retained products of conception, or pre-existing infection.2

Risk factors for PID include previous PID, no previously borne children, previous induced abortion, multiple sex partners, and pre-existing infection.3 Antibiotics are often distributed to women presenting for abortion with pre-existing Chlamydia; however, the effectiveness of this approach is highly debated.4

Adverse effects of PID include chronic pelvic pain, subfertility, infertility, and ectopic pregnancy.5 Infertility is particularly difficult to study, for reasons such as its varying diagnostic criteria and the inability to find appropriate control groups. However, it is generally agreed that women with a history of PID are at significantly increased risk of infertility.6 One study found that subfecundity increased by no less than 620 per cent among women who terminated a pregnancy.7

Finally, PID is the most common cause of ectopic pregnancy.8 Induced abortion can cause ectopic pregnancy through retained products of conception and PID.9

- Penney GC, Thomson M, Norman J, et al. A randomised comparison of strategies for reducing infective complications of induced abortion. BJOG 1998; 105(6): pp. 599-604.

- Rahangdale L. Infectious complications of pregnancy termination. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009; 52(2): 198-204, p. 198.

- Nielsen IK, Engdahl E, Larsen T. [Pelvic inflammation after induced abortion] Danish. Ugeskr Laeger 1992 September 28; 154(40): pp. 2743-6; Levallois P, Rioux JE. Prophylactic antibiotics for suction curettage abortion: results of a clinical controlled trial. AJOG 1988; 158(1): pp. 100-5; Lawton BA, Rose SB, Bromhead C, Gaitanos LA, MacDonald EJ, Lund KA. High prevalence of mycoplasma genitalium in women presenting for termination of pregnancy. Conception 2008; 77(4): pp. 294-8.

- Achilles SL, Reeves MF. Prevention of infection after induced abortion: release date October 2010 SFP Guideline 2012. Contraception 2012; 83(4): pp. 295-309.

- Sorensen JL, Thranov I, Hoff G, Dirach J, Damsgaard MT. A doubleblind randomized study of the effect of erythromycin in preventing pelvic inflammatory disease after first-trimester abortion. BJOG 1992; 99(5): p. 436.

- Torres-Sanchez L, Lopez-Carrillo L, Espinoza H, Langer A. Is induced abortion a contributing factor to tubal infertility in Mexico? Evidence from a case-control study. International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2004; 111(11): pp. 1254-60.

- Hassan MAM, Killick SR. Is previous aberrant reproductive outcome predictive of subsequently reduced fecundity? Human Reproduction 2005; 20(3): pp. 657-64.

- Tenore J. Ectopic pregnancy. American Family Physician 2000; 61(4): pp. 1080-8.

- Chung CS, Smith RG, Steinhoff PG and Mi MP. Induced abortion and ectopic pregnancy in subsequent pregnancies. American Journal of Epidemiology 1982; 115(6): pp. 879-87.

Physical complications: injury, miscarriage, placenta previa

The rate of perforation of the uterus during induced abortion is higher than often recognized. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has reported that uterine perforation during induced abortion ranges from one to four per 1000 (0.1-0.4 per cent).1 However, “most traumatic uterine perforations during first-trimester abortions are unreported or even unsuspected.”2 One study of 6408 induced abortions found a perforation rate of 15.6 per 1000 procedures.3

Perforation of the uterus can lead to infertility from Asherman’s syndrome (intrauterine adhesions), as scar tissue develops following curettage of the pregnant or recently pregnant uterus. The incidence of Asherman’s is increasing worldwide.4 The syndrome often presents as abnormal menses, infertility, or recurrent miscarriage. Among women being investigated for infertility, intrauterine adhesions were the most common abnormal uterine finding.5 Moreover, one study found that 42 per cent of women with Asherman’s syndrome had developed it after a prior D&C induced abortion.6

Another complication of the scarring caused by uterine perforation is placenta previa, which occurs when the placenta implants in the lower uterine segment, near or covering the cervix. Placenta previa increases the likelihood of preterm birth, low birth weight and prenatal death.7

Cervical trauma after induced abortion has been found to be as frequent as one in every 100.8 Dilation of the cervix during a surgical abortion can render the cervix incompetent, resulting in miscarriage or preterm births in subsequent pregnancies.

- Niinimaki M, Pouta A, Bloigu A, Gissler M, Hemminki E, Suhonen S, Heikinheimo O. Immediate complications after medical compared with surgical termination of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 114: pp. 795-804.This rate included studies by Zhou (rate: 2.3/1000), and an Australian study (rate 0.86/1000). Pridmore BR, Chambers DG. Uterine perforation during surgical abortion: a review of diagnosis, management and prevention. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1999; 39: pp. 349-53.

- Kaali SG, SzigetvariIA and Bartfai GS. The frequency and management of uterine perforations during first-trimester abortions. AJOG 1989 August; 61(2): pp. 406-8.

- Ibid.

- Yu D, Wong Y, Cheong Y, Xia E, Li T. Asherman syndrome – one century later. Fertility and Sterility 2008; 89(4): pp. 759-79.

- Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Parente RC, Lasmar BP, daRosa DB, Penna IA, Dias R. Hysteroscopic evaluation in patients with infertility. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2010 August; 32(8): pp. 393-7.

- Fernandez H, Fadheela A, Chauveaud-Lambling A, Frydman R, Gervaise A. Fertility after treatment of Asherman’s syndrome stage 3 and 4. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2006; 13: pp. 398-402.

- Thorp Jr. JM, Hartmann KE, Shadigian E. Long-term physical and psychological health consequences of induced abortion: review of the evidence. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey 2002; 58(1): pp. 67-79.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The care of women requesting induced abortion. Evidence-based clinical guideline number 7, 2004.

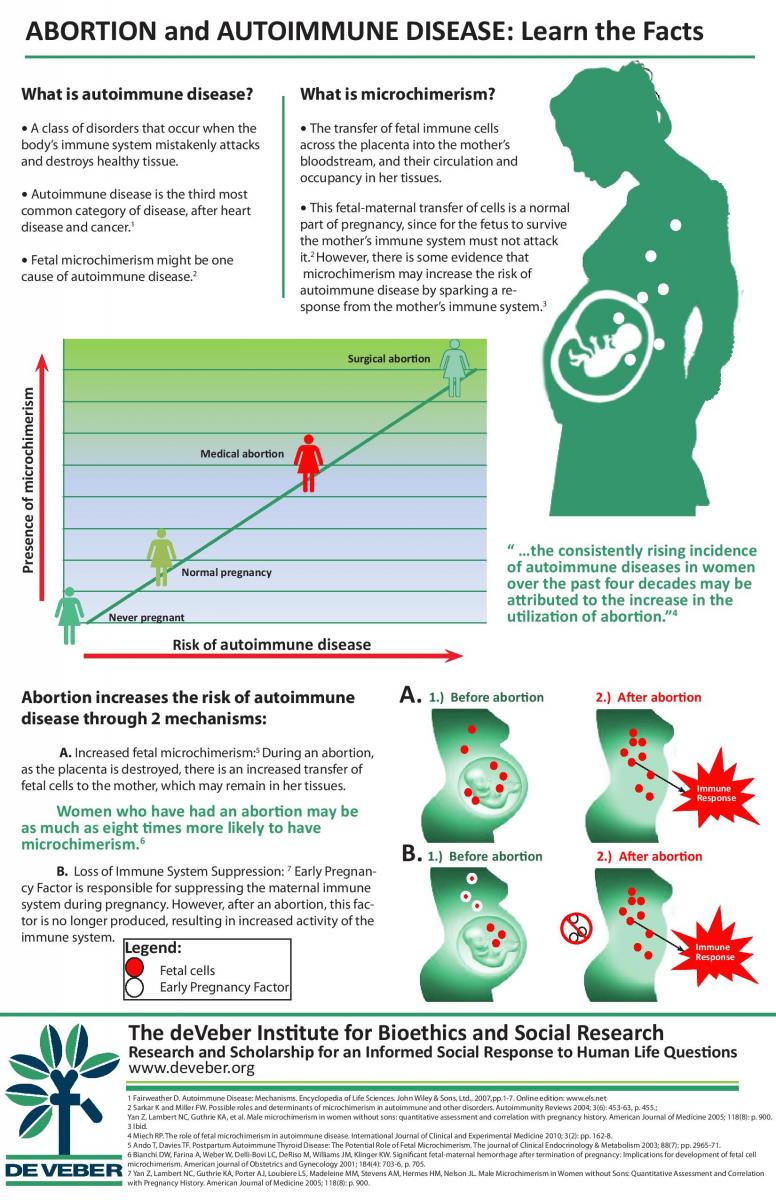

Physical complications: autoimmune disease

Autoimmune disorders occur when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys healthy tissue. Over 80 disorders have been identified, and five to eight per cent of Americans are affected by them.1 Autoimmune disorders are the third most common disease after heart disease and cancer, and their prevalence is increasing.2

Research into the causes of autoimmune disorders is ongoing. One mechanism that has been proposed is fetal microchimerism, which occurs when fetal immune cells transfer across the placenta into the mother’s bloodstream and, with a great capacity for dividing and maturing, circulate and reside in her tissues.3 Although some transfer of fetal immune cells is normal, a woman’s immune system may attack the healthy tissue where the cells have resided in a graft vs. host response, like that which takes place when a donated organ is rejected by the recipient. Fetal microchimerism is therefore a plausible explanation of the large diversity of tissue pathology and the yearly increase in autoimmune diseases in women.4

Induced abortion may be associated with autoimmune disorders through its effect on fetal microchimerism. It has been found that “women with previous induced abortion are eight times more likely to have microchimerism than other healthy women.”5 Within one hour after termination of pregnancy, there is a significant fetal-maternal transfusion of cells, which may be due to the destruction of the placenta.6 Thus, “the consistently rising incidence of autoimmune diseases in women over the past four decades may be attributed to the increase in the utilization of abortion.”7

- Progress in Autoimmune Diseases Research, Report to Congress, National Institutes of Health, The Autoimmune Diseases Coordinating Committee, March 2005. http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/autoimmune/documents/adccfinal.pdf.

- Fairweather D. Autoimmune Disease: Mechanisms. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2007, pp.1-7. Online edition: www.els.net.

- Ando T, Davies TF. Postpartum Autoimmune Thyroid Disease: The Potential Role of Fetal Microchimerism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2003; 88(7): 2965-71.

- Miech RP. The role of fetal microchimerism in autoimmune disease. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2010; 3(2): 162-8.

- Yan Z, Lambert NC, Guthrie KA et al. Male microchimerism in women without sons: quantitative assessment and correlation with pregnancy history. American Journal of Medicine 2005; 118(8): 899-906.

- Bianchi DW, Farina A, Weber W, et al. Significant fetal-maternal hemorrhage after termination of pregnancy: implications for development of fetal cell microchimerism. AJOG 2001; 184(4): 703-6, p. 705; Miech RP, 162.

- Miech RP, 162.

Chapter 11 Summary

Physical complications: maternal mortality from abortion

How likely is a woman to die after an induced abortion? This is difficult to answer since maternal deaths are underreported in the US and Canada. Due to the politicization of abortion in North America, many abortion-related deaths are attributed to other causes. Death certificates do not note the cause of death as abortion complications if the death occurred more than 42 days after the abortion. The greatest errors in death classification occur for post-abortive deaths.1

Nevertheless, four large-scale, data-linkage studies have found a significantly higher maternal mortality rate from induced abortion than from childbirth. Researchers in Finland discovered that the maternal death rate after abortion was nearly four times greater than after childbirth. They further noted that 73 per cent of all pregnancy-associated deaths could not have been identified from death certificates alone and that the suicide rate after childbirth was six times lower than the suicide rate after abortion.2 These findings are supported by studies conducted in Denmark and the United Kingdom, as well as a methodologically rigorous study from California.3

- Jacob S et al. Maternal mortality in Utah. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1998 February; 91(2): pp. 187-91.

- Gissler M, Hemminki E, Lonnqvist J. Suicides after pregnancy in Finland, 1987-94: register linkage study. British Medical Journal 1996 December; 313(7070): 1431-4.

- Coleman PK, Reardon DC and Calhoun BC. Reproductive history patterns and long-term mortality rates: a Danish, population-based record linkage study. The European Journal of Public Health 2013; 23(4): 569-74; Reardon DC and Coleman PK. Short and long term mortality rates associated with first pregnancy outcome: population register based study for Denmark 1980-2004. Medical Science Monitor 2012; 18(9): PH71-76.; Morgan CL, Evans M and Peters JR. Suicides after pregnancy: mental health may deteriorate as a direct effect of induced abortion. BMJ 1997 March; 314(7084): pp. 902-3.; Reardon DC, Ney PG, Scheurer FJ, Congle JR, Coleman PK. Suicide deaths associated with pregnancy outcome: A record linkage study of 172,279 low income American women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health 2001; 3(4 Supplement 2): p. 104.

Medical or drug-induced abortion: how safe?

Medical (chemically-induced) abortion has become more widely practiced in recent years as an alternative to surgical abortion. Medical abortion takes longer, involves artificial labour, and ends in the delivery of a dead fetus.1 The failure rate of medical abortion ranges from 4 to 16 per cent.2 Currently, the most common drug regimens are: mifepristone (RU486) combined with misoprostol, methotrexate combined with misoprostol, and misoprostol alone.

A successful medical abortion is defined as a complete expulsion of the fetus without surgical intervention. Failure can result from: 1) an incomplete abortion; 2) severe bleeding; 3) ongoing pregnancy; or 4) the patient’s request for surgical abortion. Researchers have found higher failure rates in developing countries.3 They also note that the failure rate increases with gestational age.4

Medical abortion can have various negative effects. One study found a 29 per cent rate of adverse effects (compared to four per cent for surgical abortions), including nausea, vomiting, severe stomach pain and bleeding, infection, uterine perforation and uterine rupture.5 In addition, complications such as ectopic pregnancy can occur after medical abortion. One major study found that nine per cent of women who undergo medical abortion suffer emergency complications.6 Given the many complications associated with medical abortion, women clearly deserve to be informed of these risks.

- Grossman D, Blachard K, Blumenthal P. Complications after Second Trimester Surgical and Medical Abortion. Reproductive Health Matters 2008; 16(31): p. 179.

- Jensen J, Astley S, Morgan E, Nichols M. Outcomes of Suction Curettage and Mifepristone Abortion in the United States. Contraception 1999; 59(3): pp. 153-9. See Complications: Abortion`s Impact on Women for full reference.

- Winikoff B, Sivin I, Coyaji K, et al. Safety, efficacy and acceptability of medical abortion in China, Cuba, and India: A comparative trial of mifepristone-misoprostol versus surgical abortion. AJOG 1996; 176(2): pp. 431-7

- Ibid.

- Grossman et al.

- Child TJ, Thomas J, Rees M, MacKenzie IZ. A comparative study of surgical and medical procedures: 932 pregnancy terminations up to 63 days gestation. Human Reproduction 2001; 16(1): pp. 67-71.

Multi-fetal pregnancy reduction (MFPR)

Infertile couples are often driven to turn to in vitro fertilization (IVF), wherein typically several embryos are implanted and all but one are terminated. This process, known as multi-fetal pregnancy reduction (MFPR), poses many ethical questions.

The first question is the justification for MFPR. The medical justification is that it is morally acceptable to sacrifice some “innocent” fetal lives to reduce health risks (such as prematurity) for the survivors. However, there is still debate as to whether MFPR does result in a single healthy baby. Souter and Goodwin found that “reducing triplets to twins results in significant secondary benefits: lower cost and fewer days in hospital and a decrease in a variety of moderate morbidities… However, it is not clear that couples are more likely to take home a healthy baby, if they undergo multi-fetal pregnancy reduction.”1 This is because multiple pregnancies lead to increased maternal, fetal, and neonatal health risks, even after reduction.2

The second question is whether parents are presented with the option of carrying multiple pregnancies to term. Doctors often pose the choice to parents as having, for example, four “unhealthy” babies or two “healthy” ones. Rather than offering a clear choice, some professionals give parents the sense of “having to reduce.”3 This sense of necessity does not allow for parents to choose in a way that is truly free from coercion.

Finally, what are the physical and psychological effects of the procedure? MFPR can have significant psychological outcomes. Although more research is needed, many parents unfortunately report sadness and guilt.4 This may affect their parenting style towards surviving children.5

More research is needed on the effects of MFPR, so that parents are informed and give consent freely.

- Souter I, Goodwin TM. Decision making in multifetal pregnancy reduction for triplets. American Journal of Perinatology 1998 January; 15(1): 63-71; p. 63.

- Stone J, Ferrara L, Kamrath J, Getrajdman J, Berkowitz R, Moshier E, Eddleman K. Contemporary outcomes with the latest 1000 cases of MFPR. AJOG 2008; 199(4): pp. 406.e1-4.

- Britt DW, Evans MI. Sometimes doing the right thing sucks: Frame combinations and multi-fetal pregnancy reduction difficulty. Social Science & Medicine 2007; 65: pp. 2342-56.

- Garel M, Stark C, Blondel B, Lefebvre G, Vauthier-Brouzes D, Zorn JR. Psychological reactions after multifetal pregnancy reduction: A 2-year follow-up study. Human Reproduction 1997 March; 12(3): pp. 617-22.

- McKinney MK, Tuber SB, Downey JI.Multifetal pregnancy reduction: psychodynamic implications. Psychiatry Winter 1996; 59(4): pp. 393-407.

Premature or preterm births after abortion

The link between prematurity and abortion is strongly supported by research. Women who have had one or more induced abortions have a significantly higher rate of prematurity or preterm birth and low birth weight in subsequent pregnancies. One meta-analysis found that the adjusted risk of prematurity (meaning under 37 weeks gestation) increased by 27 per cent after one abortion, and 62 per cent after two or more abortions.1 Another meta-analysis yielded similar increased risks, and also found that the risk of having a very premature delivery (meaning under 32 weeks gestation) increased by 64 per cent after an abortion.2 This link remained even after controlling for factors such as income. Other studies have yielded even higher risks of bearing a preterm child.3 This increase in risk is usually due to a weakened cervix or infections resulting from abortion.

There are various health risks associated with premature birth. Infants who do not reach a gestation age of 37 weeks have a much lower chance of reaching adulthood.4 Prematurity increases the risk of disabilities such as cerebral palsy, mental retardation, psychological and behavioural disorders, and epilepsy.5 In addition, a premature baby whose mother has had any prior abortions has a 60 per cent higher risk of cerebral palsy than a premature baby whose mother has had no prior abortions.6 Prematurity is also a major risk factor for autism. One study reported that 25 per cent of children born prematurely met autism criteria, which is five to ten times higher than the general autism rate in North America.7 A few studies have looked directly at the abortion-autism link. Burd and colleagues found that the children of mothers who had experienced one or more induced abortions had a 236 per cent increased risk of giving birth to a child with autism.8

- Shah PS, Zao J. Induced termination of pregnancy and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology May 2009; 116(11): 1425-42, p. 1439.

- Swingle HM, Colaizy TT, Zimmerman MB, Morriss FH. Abortion and the risk of subsequent preterm birth. The Journal of Reproductive Medicine 2009 February; 54(2): pp. 95-108.

- Hardy G, Benjamin A, Abenhaim HA. Effect of induced abortions on early preterm births and adverse perinatal outcomes. JOGC 2013 February; 35(2): 138-43, Table 2, p. 141.

- Moster C, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. NEJM July 2008; 359(3): 262-73, p. 262.

- Ibid.

- Jacobsson B, Hagberg G, Hagberg B, Ladfors L, Niklasson A, Hagberg H. Cerebral palsy in preterm infants : a population-based case-control study of antenatal and intrapartal risk factors. ActaPaediatrica 2002; 91: 946-51, Table 2, p. 948.

- Limperopoulos C, Bassan H, Sullivan NR, Soul JS, Robertson RL, Moore M, Ringer SA, Volpe JJ, du Plessis AJ. Positive screening for autism in ex-preterm infants: prevalence and risk factors. Pediatrics 2008 April; 121(4): 758-65, p. 758.

- Burd L, Severud R, Kerbeshian J, Klug MG. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for Autism. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 1999; 27(6): pp. 441-50, p. 447.

Pain during and after abortion

There is general agreement among medical experts that abortion can cause pain in women, and that the methods used to treat this pain are not always sufficient. Between 78 and 97 per cent of women say they experience at least moderate pain during a surgical abortion.1 Pain may vary by procedure, with suction evacuation apparently the most painful.2

Many common techniques for pain reduction may not actually work. While most studies find that conscious sedation effectively reduces pain, some disagree.3 Another common method of pain reduction is paracervical block, but one review found that there is surprisingly insufficient evidence of its effectiveness.4

The physical causes of pain during abortion are fairly well known and vary by method. Suction evacuation involves pain due to cervical dilatation and uterine contractions.5 Pain during dilation and curettage occurs during injection of the cervical block, cervical dilation, and suction aspiration.6 Pain is also associated with pre-operative anxiety.7

Pain during abortion may be linked to psychological problems after abortion. One study found that patients receiving local anaesthesia reported more pain and more depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress symptoms than patients receiving intravenous sedation.

Despite this evidence, women are often uninformed about abortion pain. Many women are mistakenly told that the pain will be similar to menstrual cramps.8 In addition, physicians often underestimate the amount of pain experienced.9

- Renner RM, Jensen JT, Nichols MD, Edelman AB. Pain control in first-trimester surgical abortion: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Contraception 2010 May; 81(5): 372-88, p. 372.

- Singh RH, Ghanem KG, Burke AE, Nichols MD, Rogers K, Blumenthal PD. Predictors and perception of pain in women undergoing first trimestersurgical abortion. Contraception 2008 August; 78(2): pp. 155-61.

- Wong CYG, Ng EHY, Ngai SW, Ho PC. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study to investigate the use of conscious sedation in conjunction with paracervical block for reducing pain in termination of first trimester pregnancy by suction evacuation. Human Reproduction 2002 May; 17(5): pp. 1222-5.

- Renner et al., p. 372.

- SikYauKan A, Caves N, Yuen Wai Wong S, Hung Yu Ng E, Chung Ho P. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial on the use of a 50:50 mixture of nitrous oxide/oxygen in pain relief during suction evacuation for the first trimester pregnancy termination. Human Reproduction 2006 October; 21(10): pp. 2606-11.

- Meckstroth KR, Mishra K. Analgesia/Pain Management in First Trimester Surgical Abortion. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009 June; 52(2): 160-70, p. 160.

- Pud, D, Amit A. Anxiety as a Predictor of Pain Magnitude Following Termination of First-Trimester Pregnancy.Pain Medicine 2005 March; 6(2): 143-8, p. 146.

- Hamoda H, Flett GMM, Ashok PW, Templeton A. Surgical abortion usingmanual vacuum aspiration under local anaesthesia: a pilot study of feasibility and women’s acceptability. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 2005 July; 31(3): pp.185-8.

- 9.Dean G, Cardenas L, Darney P, Goldberg A. Acceptability of manual versus electric aspiration for first trimester abortion: a randomized trial. Contraception 2003 March; 67(3): pp.201-6.

Psychological outcomes: abortion and family formation

One aspect of legalized abortion that has received surprisingly little attention from media and academic sources is its impact on families. Contrary to popular belief, the legalization of abortion is correlated with an increase in single-parenting. While the annual rate of abortions among unmarried women rose from 100,000 to 1.25 million with the legalization of abortion, the annual birth rate among unmarried women also rose from 322,000 to 715,000.1 Researchers suggest that the legalization of abortion changed the societal perception of premarital sexual relations and marriage.2 This led to an increase in premarital sexual relations and in pregnancies, both generally and among women who would not obtain an abortion but were pressured into premarital sex by society’s expectations. Furthermore, access to abortion made it less likely that a man would marry his pregnant girlfriend if she chose to keep the baby.3

Abortion may have a substantial impact on relationships and marriages. It increases the odds of separating, divorcing, never marrying, or marrying older.4 Surprisingly, legalized abortion also appears to have contributed to an increase in child abuse. This may be for several reasons, including the psychological effects of abortion such as grief, guilt, or mental health problems such as anxiety and depression.5 Another striking if counter-intuitive finding is that “unwanted” children (whose mothers were denied abortion) fare almost as well as those who are “wanted”.6

Finally, abortion may have affected family formation through the “feminization of poverty”. Poverty has been and continues to become an increasing problem among women, with three-quarters of the poor being women and children. This has especially been the case after the legalisation of abortion, which has led to an increase in single-motherhood and psychological problems.

- Akerlof GA, Yellen JL, Katz ML. An analysis of out-of-wedlock childbearing in the United States. Quarterly Journal of Economics 1996; 111(2): pp. 277-317.

- Ibid., p. 280.

- Brake E. Fatherhood and Child Support: Do Men Have a Right to Choose? Journal of Applied Philosophy 2005 March; 22(1): 55-73, p. 56.

- Barnett W, Freudenberg N, Willie R. Partnership after induced abortion: a prospective controlled study. Archives of Sexual Behavior 1992 October; 21(5): pp. 443-55.

- Coleman PK, Rue VM, Coyle CT, Maxey CD. Induced Abortion and Child-Directed Aggression among Mothers of Maltreated Children. Internet Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatology 2007; 6(2), http://www.ispub.com/journal/the-internet-journal-of-pediatrics-and-neonatology/volume-6-number-2/induced-abortion-and-child-directed-aggression-among-mothers-of-maltreated-children.html.

- Schüller V, Stupkova E. The unwanted child in the family. International Mental Health Research Newsletter Fall 1972; 14(3): 2-16, p. 8.

Depression, suicide, substance abuse

Research on the mental health effects of abortion is controversial, especially because of its political implications and methodological issues such as attrition. The weight of evidence, as well as women’s testimonies, supports the conclusion that for a significant minority of women, abortion has a devastating psychological impact. A recent meta-analysis by Coleman discovered an overall 81 per cent greater risk of mental health problems (including anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and suicidal behaviour) for women who had an abortion compared to those who did not.1 She also calculated the overall population-attributable risk to be 9.9 per cent, meaning that nearly 10 per cent of all mental problems experienced by women are attributable to abortion alone. Coleman’s methodology was sharply criticized by other researchers but without substantive evidence. Several studies have found results similar to Coleman’s.2

Coleman criticizes previous meta-analyses which concluded that abortion poses no greater risk to a woman’s mental health than does carrying an unintended pregnancy to term. Her reasons are threefold: 1) some pertinent literature was excluded from previous meta-analyses without explanation; 2) there was a lack of “sufficient methodologically based selection criteria;”3 and 3) there was no quantification of effects.

The Academy of Royal Medical Colleges published its own review which found a lack of correlation between abortion and mental health problems. The report also acknowledged that other factors could trigger mental health problems related to abortion, “such as pressure from a partner to have an abortion and negative attitudes towards abortions in general and towards a woman’s personal experience of the abortion.”4 Unfortunately, the Report has a number of serious flaws that render its findings questionable. Many sound studies are ignored, while others are dismissed for vague or inappropriate reasons. Its conclusions are based on a very small number of studies that are not properly rated for quality. This has resulted in women being misinformed about the potential negative impact of abortion.

In short, the evidence is very strong that, for a significant minority of women, abortion has a devastating psychological impact.

- Coleman PK. Abortion and mental health: quantitative synthesis and analysis of research published 1995-2009. British Journal of Psychiatry 2011; 199(3): pp. 180-6; 200(1): pp. 77-80.

- E.g. Morgan CL, Evans M, Peters JR. Suicides after pregnancy. Mental health may deteriorate as a direct effect of induced abortion. BMJ 1997 March; 314(7084): pp. 902-3; Mota NP, Burnett M, Sareen J. Associations between abortion, mental disorders, and suicidal behaviour in a nationally representative sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2010; 55(5): 239-247, p. 241.

- Coleman, p. 181.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH). Induced abortion and mental health: a systematic review of the mental health outcomes of induced abortion, including their prevalence and associated factors. London: Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, December 2011.

Intimate partner violence and abortion

Also known as Domestic Violence, “Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is defined as threatened, attempted, or completed physical or sexual violence or emotional abuse by a current or former intimate partner.”1 Each year, IPV “results in an estimated 1200 deaths and two million injuries among women” in the United States.2

Studies worldwide report a correlation between IPV and abortion, revealing that women who suffer from intimate partner violence are more likely to have an abortion—both induced and spontaneous—than those who do not.

Abuse is often triggered or amplified by pregnancy. IPV directed towards pregnant women may cause miscarriage, whether intentionally or accidentally. Hence, there should be more screening for abuse during pregnancy.

Unintended pregnancy is more common in abusive relationships, where forced sex and rejection of contraception is more likely; and unintended pregnancies are typically those sought to be terminated. At the same time, however, abortion-seeking women who have experienced IPV are more likely to have been coerced to terminate their pregnancy. Thus, health professionals should be aware that a woman’s termination of pregnancy may not be her free choice.3

Some research also indicates that women who have had an induced abortion may subsequently experience or exacerbate IPV. One Indian researcher found that “as the proportion of intervals in which abortion occurred increases, the odds of experiencing violence increases significantly.”4

- Black MC, Breiding MJ. Adverse Health Conditions and Health Risk Behaviors Associated with Intimate Partner Violence—United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2008; 57(5): p. 113.

- Ibid.

- Keeling J, Birch L, Green P. Pregnancy counselling clinic: a questionnaire survey of intimate partner abuse. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 2004; 30(3): p. 166.

- OR 3.74; Lee-Rife SM. Women’s empowerment and reproductive experiences over the lifecourse. Social Science & Medicine 2010; 71(3): p. 639.

Who are the experts? What 101 women told us

Narrative research is an increasingly recognized field in psychology and medicine.1 However, the professional literature rarely, if ever, includes narratives of post-abortive women.

In 2008, the American Psychological Association (APA) disseminated a report on the psychological impact of abortion on women, which concluded that the research did not support the existence of post-abortion psychological distress.2 Yet, the APA task force failed to address the narratives of thousands of women who have experienced psychological distress after abortion, despite the fact that many US courts have accepted the validity of affidavits from such women.

The overwhelming force of testimonies from large numbers of post-abortive women continues to challenge the common assumption that induced abortion is safe, easy, and uncomplicated. Among 101 women who told the deVeber Institute their stories, many reported a lack of informed consent and pressure or coercion to abort; moreover, all testified to the devastating impact of abortion in terms of depression, broken partner relationships, and the resort to alcohol and other non-medical substances.

- Stevens PE. Marginalized women’s access to health care: a feminist narrative analysis. Advances in Nursing Science 1993 December; 16(2): p. 41.

- American Psychological Association Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion (August 2008). Task Force – Brenda Major (Chair), Mark Appelbaum, Linda Beckman, Mary Ann Dutton, Nancy Felipe Russo) Report available at http://www.apa.org/pi/wpo/mental-health-abortion-report.pdf. See also Adler NE, David HP, Major BN, Roth S, Russo N, Wyatt G. Psychological responses after abortion. Science 1990 April; 248(4951): pp. 41-4.

Women’s voices: narratives of the abortion experience

The deVeber Institute collected the narratives of 101 post-abortive women and organized its findings into three parts. First is a detailed account of one woman’s experience of abortion in a developing nation. Her story sheds light on the coercive pressures currently placed on women, regardless of education or status, to limit the number of children they bear. These pressures were exerted not only by her husband, but also by her parents, employers, friends, and medical personnel.

The second section synthesizes the results of 92 interviews with post-abortive women from Canada and the United States. While these women may have undergone an abortion anywhere from three to sixty years prior, the results of the study indicate that a vast majority of the women found their abortion to be an “emotionally devastating experience,” and all regretted having the abortion.

The final section details eight stories from post-abortive women approaching the end of life, indicating that a significant number of women experience acute spiritual pain on their deathbed stemming from an earlier abortion.

In light of these testimonies, it is clear that the characterization of abortion (often found in the scientific literature) as a ‘minor operation’ may be directly challenged. In addition, these narratives indicate that the notion of abortion as ‘a woman’s choice’ is illusory for many. Over two-thirds of the women who answered the question said that if they had not been pressured and/or coerced, and had received at least minimal support from medical personnel or significant others, they would not have had the abortion. Every one of the women who shared her story stated that if she had it to do over again she would go through with the pregnancy, and all but one would counsel others not to have an abortion, no matter how difficult the circumstances.